Introduction to French regional jewellery

French regional jewellery - Introduction

Industrialisation came early to France, compared with other European countries and both Paris and Lyon became important centres of mass-produced jewellery by the middle of the 19th century. Stamped rings, brooches and crosses could be made far cheaper and lighter than cast versions and an efficient system of distribution ensured that large quantities could be disseminated across France quickly. Jewels were wholesaled out to retail jewelers and also to travelling salesmen who sold jewellery door-to-door as well as at the regular fairs and religious assemblies.

Many of the jewels were made of rolled-gold, in which a “sandwich” consisting of a plate of copper between two thin plates of gold is compressed between rollers to the required thickness and then stamped into the form of the jewel. Companies such as Fix, Murat and Oria, founded in 1829, 1847 and 1867 respectively, specialized in high quality rolled gold jewellery. For the first time in history the common person could wear a jewel that looked like it was made of gold and the demand was strong during the mid-nineteenth century in an increasingly wealthy France. The popularity of gold plated jewellery stimulated the demand for real gold jewellery among those who could afford it, and while some solid gold jewellery was made industrially, a good proportion was made locally, especially the regional jewellery.

There are, in fact, three types of French regional jewellery. The first type is the jewels that were worn in the heyday of regional jewellery, between 1750 and 1840. These jewels would have evolved from a humble ring or cross into something unique to that region by a process of successive and perhaps almost imperceptible mutations and adaptations. Regional, or folk jewellery, is defined by a particular style confined to a particular region. Some jewels were made in Paris or Lyon but worn only in a certain region, in which case they qualify as regional jewels. Other jewels which were made in a particular region but worn throughout France cannot be considered regional. Some regional jewels were an integral part of folk costumes, indeed some were sewn to the costumes, while others were worn in certain regions but with ordinary clothes.

The International Exhibition of London in 1872 saw many countries display their traditional 'peasant' jewellery on their stands and France was no exception with a large display of costumes and jewellery from Brittany. This stimulated a fashion in England where there was no tradition of regional jewellery and soon many of the wealthier English women were wearing and collecting European regional jewels. French manufacturers restarted production of regional jewellery and soon English jewelers started copying them. The fashion spread to France and today it can be difficult to determine if a nineteenth century jewel was worn as part of a traditional costume or during a passing fad. These revival jewels can be considered a second type of regional jewellery. They can be similar, even identical to the earlier types but their use was not the same. The advent of the railway brought increasing numbers of tourists to the French provinces and local jewellers were quick to seize the opportunity to sell them regional jewels, both antique and newly made. The pardon pins and fibulae of Brittany were particulary popular with tourists, despite the fact that the majority were in fact produced in Bohemia.

The Camargue cross was created in 1926, the Pentacrine-set jewels from Digne around 1850 and the flowered crosses of Savoy around 1880. Even today, the flowered cross continues to evolve and some Savoy jewelers reproduce the altar cross of local churches in gold or silver to make new regional crosses for tourists.

Reproductions of the antique regional jewels are still made today, often by the same manufacturers of the third type mentioned above, however they tend to be smaller and less flamboyant than the most spectacular antique regional jewels. Some of the larger jewels are still sold to members of folkloric dance groups, who are unable or unwilling to invest in and wear the costly antique regional jewels, or to persons who just want to buy them to keep alive the tradition and for their beauty and history. Some towns and villages have annual regional costume days where the locals dress up in their finest antique or reproduction regional outfits and circulate around town to be admired and photographed.

Saint Lô cross in silver and Rhinestones where the polished-off culets have been imitated by black painted spots

At the end of the 19th century, the Parisian jewellers making French regional jewellery would do their best to make them look as antique as possible. Because on genuine antique diamonds and Rhinestones the bottom point of the stone, the culet, was polished off, in order to make the modern cut stones they were using look like the antique ones, the jewellers would paint a black spot on the culet of the stone.

The third type of French regional jewellery consists of jewels that have been made recently without traditional motifs and are worn to express one’s solidarity with one’s region. Brittany has probably the most active regional jewellery market today and the Celtic symbols such as the triskelion (triskèle) are popular on jewellery, much of which is made of silver and bought by young people or tourists. Alsace has its stork motif, Lorraine the thistle, the Camargue region the bull, Champagne the grapes and so on.

The study of French regional jewellery

The study of regional jewellery is a fascinating pastime. There is still so much to be discovered, all that is required is to constantly observe, research and absorb all that is possible and then wait for new discoveries, ideas and conclusions to come to the forefront. For instance, one cannot, as some authors have done, draw any conclusions as to the popularity of a jewel in the past by simply looking at the frequency with which the jewel is found today. Of course the latter can be a clue, but it is without value unless other, much more important factors are taken into account.

|

"fileuses" ear pendants

in rolled gold

|

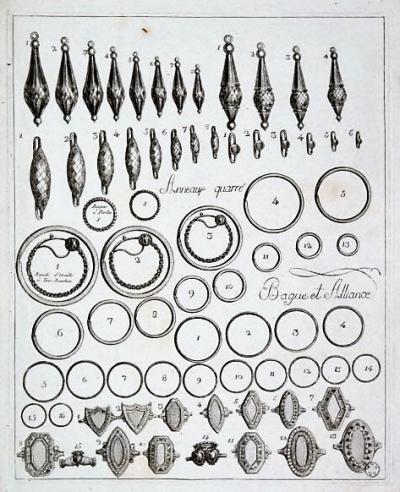

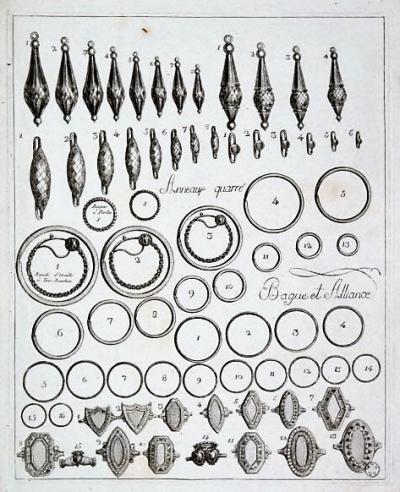

As an example, the Polletaise (fileuses) ear pendants and the filigree ear pendants of the Dieppe region are extremely rare today yet seem to have been very common in the nineteenth century based on the iconographic evidence. A page of designs by the 19th century manufacturing jeweller Baudet shows no less than fourteen different sizes of Polletaises (fileuses) earrings available. (2) Although one cannot draw any firm conclusions from the study of prints and photos, the explanation for the scarcity of these jewels today is quite simple if you have an experience of the jewellery market. These earrings were made of stamped gold, which implied a jeweller somewhere making several metal dies in solid steel. The earrings were cheap to make as long as the steel dies existed, but they were very difficut to repair as they were hollow and very light. Once the steel die was broken or too worn to be used, production stopped unless the demand was sufficient for a new die to be engraved. It is very likely that women continued to wear these earrings for some time after production had stopped and thus gradually all the earrings became worn, broken or were lost until only a very small number survived. Earrings are of course much more vulnerable to loss than rings, necklaces or brooches and if one is lost or broken, the remaining one will be rapidly sold or melted. |

ear pendants from

Dieppe in gold

|

Catalogue from Baudot, Paris, Empire period.

There are still some companies in France who make and use dies for stamping jewellery, and they have the most wonderful collections of nineteenth century dies which they will re-use if you place a reasonable order. But they have no dies for the Dieppe earrings, nor indeed for the Jeannette cross, which was once the most popular cross in France. How could it be that they have no dies of such a popular cross? The explanation is again quite simple: they continued to produce these crosses until the last die broke and no one today is prepared to pay them the several thousand euros it will cost to carve a new pair of dies. So although Jeannette crosses are still made today, they are cast in moulds rather than being stamped. This makes for a more expensive cross as the gold weight is higher but the investment for the jeweller is far lower.

Many other jewels can be readily repaired and thus have survived 150 or 200 years in family collections. But the heavier a jewel is, the more likely it will be that an owner will melt or trade in a damaged or unfashionable jewel at some time. Gold has always been expensive, and even with the recent rises in the gold price, gold jewellery is still more affordable than it was a hundred years ago. The booms in the gold price in 1980 and 2011 saw an enormous amount of antique jewellery melted and it's not true that jewellers refrain from melting rare regional jewels: many don't recognise them for what they are or don't want to go through the hassle of repairing and selling them separately, it's so much easier to melt everything once a week.

I have seen with my own eyes how little knowledge many jewellers have of the history of jewellery and as for the cowboy gold-buyers who enter the market whenever there is a boom, everything they buy is immediately melted. Some of my best pieces were obtained by buying all the jewellery from inexperienced gold-buyers at the same price the smelters were offering and then sorting it. When I ask jewellers if they ever have any regional jewellery, most of them say no, but when I show them pictures, they generally agree that they have seen regional jewels and melted them. The French customs authorities terrorise gold dealers with their unannounced raids during which they will confiscate anything that hasn't been hallmarked or clearly identified in the second-hand book. Many gold buyers have given up trying to comply with constantly changing requirements set by the customs officers and prefer to just melt everything. How much of our heritage has been destroyed by such over-zealous inspections will never be known....

As each generation gives way to the next and jewels are passed on, the recipient looks at the inherited jewellery with a critical eye : Will I wear it? Does it have any sentimental value? Is it pretty? What can I get for it? It is evident that a pretty jewel with a high sentimental value has more chance of being kept for future generations than an unfashionable or worn-out jewel with little sentimental value and a high intrinsic (metal) value.

Trying to determine the popularity of jewels by looking at the iconographic evidence is tempting, however there are few records and one can assume that the persons able to afford to have a painting of themselves made did not represent the general population. And just like today, when a woman in Morocco or Algeria will hire jewellery to wear for her wedding if she cannot afford to buy it, we cannot deduce what was worn by the everyday woman in the street from the photos and Daguerreotypes. Lanté and Gatine, when they set out to document the costumes worn by the women in Normandy in 1811, admitted that many of the costumes were no longer regularly worn by then, and they had to convince some women to bring them out of storage in order to sketch them. (3)

The only way to really find out which jewels were the most popular is to continue to observe and filter all the information which is at hand: records kept by manufacturers, anecdotes and observations in contemporary references and novels, photographs, hoards of jewels, finds made by metal detectorists, in short all the scraps of information a detective would use to solve a mystery. The work done by Marguerite Bruneau in examining hundreds of notarial acts in Normandy from the seventeenth and eighteenth century is remarkable and proof that hard slogging can get results.

Another area of study is to try and determine the exact areas in which a particular style of jewellery was worn and made. Most antique jewels on the market today have no indication of their provenance, and yet this is so important. If I buy a cross in Rouen I will try and find out from the seller where she obtained it and with luck I might be told that it was inherited from a grandmother who lived in Criqueboeuf sur Seine. This is important information, but even if I can't find out the history, the fact that it was bought in Rouen is always a good indication and should be noted. Of course families can move, or even collect jewels frbut perhaps 90% of jewels haven't moved far and the place one buys a jewel is always worth noting down. The largest croix de Saint Lô I ever bought was purchased in Epinal, perhaps as far away from Saint Lô in Normandy as you can get in France, and the seller was incapable of telling me how her family had obtained it. Hallmarks, where clearly visible, can in many cases identify the actual town in which the jewel was made.

|

The evolution of regional jewellery is another field with much to be discovered. I have set out on this site how I believe the croix de Rouen evolved from the simple croix drille, but the story of how the croix drille, the croix de Saint Lô and the croix de Caen evolved still needs to be discovered. To do this one needs to study all the jewels and photos possible to try to discern the subtle differences between them and with luck the hallmarks might help to date the various varieties. |

"poissardes" in mother-of-pearl

and steel converted into a

pair of brooches |

|

"poissardes" in mother-of-pearl

and gold |

very large and rare poissardes in gold

early 19th century

|

Poissardes in gold

|

|

|

I believe that the poissarde ear pendants started out as simple polished mussel shells worn by fishmongers as a sign. With the inevitable evolution of jewels they were circled with brightly cut steel, then gold and were finally made entirely in gold, like the ones shown below. They finally evolved into the poissardes shown at the exteme right, where the oval shape of the mussel shell is but a distant memory.

|

It's also worth bearing in mind something that is all too often forgotten. The antique photos and postcards we see often show elderly women wearing the folk costumes and regional jewellery. The folklore clubs and dancing associations often lean towards an elderly membership and viewing public. But fashion is driven by the younger generation, and as the prefect of Normandy wrote in 1801, it was the younger women, especially those who frequented the markets, who drove the fashion for the high coiffes (lace head-dresses) for which Normandy became famous. (4) Two hundred years ago market days were the equivalent of the fashionable high streets of today, they were where one went to see and be seen. Regional jewels and costumes were fashion items.

Most collectors of French regional jewels content themselves with amassing as many objects as quickly as possible, often neglecting to research their subject sufficiently. Some take the time to find and consult the various references available and some even do some original research of their own. Regrettably, some of the latter jealously keep their findings to themselves. Where would we be today if the pioneers of science, medicine, physics and engineering had kept their discoveries to themselves rather than sharing them with the world? This site exists to share freely as much as is known about French regional jewellery as possible and I thank the collectors who regularly keep me informed of the results of their research and send me photos of their collections and finds. I encourage other collectors to do the same, and give back to this hobby a part of what it has given to you.

The market for antique French regional jewellery is a small niche, and it's complicated for a jeweller to find a buyer unless he has a client already or has the time to use the internet. For a collector, it's a costly and time-consuming hobby to try to build up a complete collection and few have attempted it. Whilst some regional jewels can't easily be worn today, many can if only more women displayed a bit of originality. Henri Clouset wrote in 1934 "if we could make the young generation understand that even on a dress of the latest fashion, a jaseron chain, a Jeannette cross and a Normandy slide are just as fashionable as a fantasy jewel made in a factory in the Marais." (5) French regional jewels are a part of our history, and whilst they may not be able to speak and tell us all they have seen, they are remarkable witnesses to our past cultural identity. An exhibition, like the one organised in 1997 and which was staged in several museums throughout France, has the power to enchant the public and stimulate collectors. Another similar exhibition is long overdue.

Mike

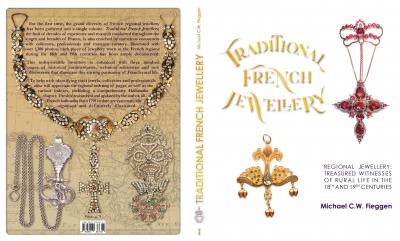

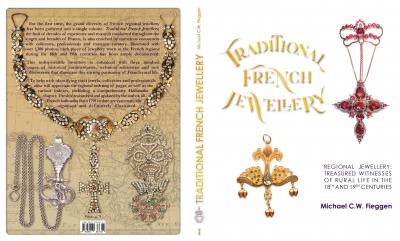

Many other jewels not visible on this website can be found in the book Traditional French Jewellery, in English - You can order it here direct from the author

|

Rapid identification guide for French regional crosses

Cross without Christ

articulated – North, Normandy, Languedoc Roussillon, Provence, Savoy

with arms of equal length - Savoy

with pendants – Béarn & Pyrénées, Brittany, Centre, North, Savoy

with diamonds – North, Picardy, Provence

with garnets or citrines – Auvergne, Languedoc Roussillon

with Rhinestones – Auvergne, Béarn & Pyrénées, Normandy, Provence

rod cross - Burgundy, Savoy

enamelled – Alsace, Languedoc Roussillon, Provence, Savoy

with filigree – Béarn & Pyrénées, North

with rays - Savoy (the flowered cross)

flat – Brittany, Centre, Dauphiné, Poitou, Provence, Savoy

reliquary - Brittany

tubular – Brittany, Savoy

_________

Croix with Christ and without Mary

simple or openworked - Dauphiné, Savoy

with grains - Champagne, Ile-de-France

with pendants – Auvergne, Centre, Limousine, North

hollow with lens decor - Ile-de-France

hollow and flat - Provence

solid – Alsace, Champagne, Lorraine

tubular - Languedoc Roussillon, Savoy

_________

Croix with Christ and Mary

simple or openworked - Alsace, Brittany, Centre, Savoy

enamelled – Auvergne

with pendants – Auvergne, Brittany, Centre, Limousine,

with rays – Brittany, Centre, Champagne, Savoy

reliquary- Brittany, Centre

|

(1) FERRY, Bruno., L’art patriotique face à l’annexion - Alsace-Lorraine -1871-1918. Editions du quotidien, Strasbourg, 2015.

(2) Planche de dessins de la Maison Baudet, 1810-1820, Michel Yvon

(3) LANTE et GATINE., Costumes des femmes du pays de Caux et de plusieurs autres parties de l'ancienne province de Normandie, le Goupey, 1827

(3) SAINT-AMAND, MASSON., Mémoire statistique du département de l'Eure, adressé au ministre de l'Intérieur d'après ses instructions par M. Masson Saint-Amand, préfet de ce département, publié par ordre du gouvernement. A Paris, de l'imprimerie impériale, an XIII

(4) CLOUSOT, Henri., Les Bijoux Populaires, Le Figaro, jeudi 9 août 1934

French regional jewellery - Introduction